| Clinical Infection and Immunity, ISSN 2371-4972 print, 2371-4980 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Clin Infect Immun and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://cii.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 10, Number 1, March 2025, pages 18-23

Platelet Counts Variation and Platelet Indices According to the Severity and Outcome of COVID-19

Abou Koundioa, b, d , Marie Lea Kaboub, Awa Oumar Tourea, c

aHaematology Laboratory, Aristide Le Dantec Hospital, Dakar, Senegal

bHaematology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Pharmacy and Odontology, Dakar, Senegal

cBiology Unit, National Blood Transfusion Center, Dakar, Senegal

dCorresponding Author: Abou Koundio, Haematology Laboratory, Aristide Le Dantec Hospital, Dakar, Senegal

Manuscript submitted April 16, 2024, accepted July 22, 2024, published online February 6, 2025

Short title: Platelet Counts and Indices of COVID-19

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/cii178

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by infection with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus, is characterized by various biological changes, notably hematological. The value of platelet count and its indices in the evolution of the disease has been raised by several authors. Our objective was to evaluate the variation in blood platelet counts and indices in relation to the progression of COVID-19.

Methods: We conducted this retrospective study between May 12, 2020 and March 20, 2021 at the Epidemiological Treatment Center and Hematology Laboratory of Aristide Le Dantec Hospital. Patients who were tested positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and who had undergone at least one complete blood count on admission were included. Excel 2019 and SPSS v.20 were used for data processing.

Results: A total of 332 patients were included with a median age of 60 years (12 - 100 years). The male gender was more represented with 58.1%. Forty-nine (49) individuals (14.75%) of the patients included in this study were seriously ill, and 39 (11.75%) of them died. The majority of our 82.8% had normal platelet counts, while only 8.4% had thrombocytopenia. The later was even more frequent in patients with poor prognosis of COVID-19 disease (11.88% versus 7.35%). Platelet indices were significantly higher in the severe group than in the non-severe group. However, only the platelet distribution width (PDW) was significantly increased according to the severity of COVID-19 disease.

Conclusion: According to our observations, PDW is an important marker in the risk stratification, the prognosis and unfavorable evolution of COVID-19.

Keywords: Platelet; MPV; PDW; SARS-CoV-2

| Introduction | ▴Top |

In December 2019, an outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) occurred in Wuhan, China, and rapidly spread worldwide. COVID-19 presents with complicated clinical manifestations, ranging from flu-like symptoms to multi-organ failure. Severe cases, especially critical cases, are usually complicated by other organ dysfunctions, including septic shock, heart failure and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) [1-3].

Regarding the hematological aspect, SARS-CoV-2 infection can cause numerous abnormalities including neutrophil-predominant hyperleukocytosis, lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia. The latter is clinically associated with thrombotic manifestations of COVID-19. Although several studies have reported that decreased platelet counts are associated with severe COVID-19 and high mortality, few have systematically assessed hematological and coagulation parameters in patients with severe COVID-19. Furthermore, the mechanisms by which this coronavirus interferes with the hematopoietic system are still not identified. However, the combination of thrombocytopenia and increased thrombotic risk, including arterial thrombotic events, raises the possibility of platelet hyperreactivity as a contributing factor in some patients with COVID-19. Since, specific parameters such as platelet count and its indices such as mean platelet volume (MPV) reflecting the average size of platelets, platelet distribution width (PDW) which represents the variation in size between different platelets and plateletcrit (PCT) which shows the volume occupied by platelets in whole blood, can be used as a direct indicator of organ dysfunction [4]. Indeed, these indices are determinants of platelet function, most of which are easily assessed by blood count. It is therefore a priority to find effective hematological parameters for risk classification. Amid this context, we conduct this study to assess the variation in platelet count and its indices regarding the severity and mortality of COVID-19.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Study design

We conducted a retrospective study of clinical data from patients with diagnosed COVID-19 admitted between May 12, 2020 and March 20, 2021.

| Study population | ▴Top |

This study included patients who were tested positive for SARS-COV2 by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), admitted to the Epidemiological Treatment Center of Aristide Le Dantec Hospital and who had benefited from a standard biological check-up of COVID-19 including at least a blood count carried out in the Hematology Laboratory of Aristide Le Dantec Hospital.

The patients were divided into two groups according to the clinical severity of the infection (severe and non-severe) and two groups according to the disease outcome by favorable or unfavorable course.

Biological analysis

From each patient, 4 mL of whole blood was collected in an ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) tube, which was quickly transported to the laboratory for a blood count. This test includes platelet count and platelet indices (MPV, PDW and PCT) among other parameters.

Statistical analysis

Excel software was used to collect sociodemographic, clinical and biological data. SPSS version 20.0 was used for data analysis. Categorical variables are reported as frequencies (percentages and 95% confidence interval (CI)) and continuous variables as means and standard deviation (SD). Chi-square, Fisher’s and analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were performed according to the conditions of applicability for the comparison of the different groups and a P-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Ethical considerations

Biological tests for patients admitted to the Epidemiological Treatment Center were carried out free of charge with strict respect for anonymity. Every precaution has been taken to protect the privacy of included patients and the confidentiality of their personal information. The study was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards set by the Declaration of Helsinki (1964).

| Results | ▴Top |

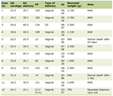

Overall, this study included 332 patients with a median age of 60 years (12 - 100 years). Male gender was more represented with 58.1% and a sex ratio (M/F) of 1.4. Most patients were aged 60 or over (50.9%), while those under 30 represented only 8.4% of patients. Among the 332 patients, the majority (168 patients or 50.6%) had a mild form of COVID-19 disease. One hundred and one individuals (30.42%) included in this study were severely ill and admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) and 39 of them died or 11.75% (Table 1). Men tended to have more severe cases of COVID-19 than women (39.9% versus 17.3%) according to the clinical severity classification. The same trend was also found when comparing the group of patients over 60 years of age with the group of younger patients (Table 2). We recorded a higher number of deaths in male patients (31 patients or 79.5%) and those over 60 (32 patients or 82.1%). Thus, gender and advanced age were significantly associated with COVID-19 disease-related mortality (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

Click to view | Table 1. Distribution of Sociodemographic, Clinical and Biological Characteristics of Patients |

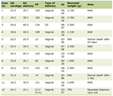

Click to view | Table 2. Difference in Age, Gender, Clinical Forms, and Platelet Count and Indices Between Severe and Non-Severe COVID-19 Patients |

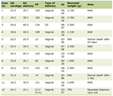

Click to view | Table 3. Difference in Age, Gender, Clinical Forms, and Platelet Count and Indices Between Survivors and Non-Survivors of Patients With COVID-19 |

Although the platelet count was not associated with the severity of the disease in our series with a P-value greater than 0.05, thrombocytopenia was nonetheless more frequent as the prognosis of COVID-19 disease was poor, ranging from 7.4% of non-severe forms to 11.9% of severe forms of the disease (Table 2).

The same trend was observed for the course of the disease: we found a higher frequency of thrombocytopenia in the group of patients who did not survive (15.4%) compared to only 7.9% of thrombocytopenia in the second group (Table 3).

Platelet indices were significantly higher in the severe group compared to the non-severe group. However, only PDW was significantly increased by disease severity in COVID-19, ranging from an average of 12.75 in the mild form to an average of 14.91 in the severe form. None of the other platelet constants showed a difference between the severe and non-severe groups (Table 2).

Platelet indices were significantly higher in the group of patients who died compared to those who survived. However, only the increase of PDW was significantly related to the unfavorable disease outcome (Table 3).

| Discussion | ▴Top |

The majority of our patients had mild to moderate forms of COVID-19, and about 30% had severe to critical symptomatology. Patients with mild or moderate COVID were still hospitalized at the start of the pandemic (early March 2020) in our center, and a standard workup including platelet count was routinely performed.

Platelet count is a simple, affordable and readily available biomarker, and it has been independently associated with disease severity and mortality risk in ICUs [5, 6]. It has been rapidly adopted as a potential biomarker for COVID-19 patients. Platelet counts were reported to be significantly reduced in COVID-19 patients and were lower in non-survivors [7-9]. Yang et al reported a frequency of thrombocytopenia of around 20% in their respective studies [10, 11]. These frequencies of thrombocytopenia were much higher than the one found in our study which was of 8.7%. Thrombocytopenia was significantly associated with mortality in Yang et al’s study [10]. However, this significant association was not found in our study and even in those of Guclu and Ozacelik [10-12]. In our study, we found that the frequency of thrombocytopenia increased with the severity and unfavorable course of COVID-19 disease. However, this difference was not significant. Similar to our study, other studies have also found normal platelet values in many patients at the time of hospital admission [5]. In contrast, several other studies have found a significant association between thrombocytopenia and both the severity and mortality associated with COVID-19 disease. These differences between studies may be related to the timing of the tests. Similarly, treatment with hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin and enoxaparin has been initiated in most countries when COVID-19 is suspected. These drugs can cause thrombocytopenia. This may be a reason for the difference observed between studies [9, 13, 14].

It has been reported in these studies that mortality increases as the platelet count decreases. In addition, platelet counts decreased in patients with progressively severe disease. The decrease in platelet count, which reflects their consumption and generation of thrombin, is useful in recognizing the presence and severity of coagulopathy.

A potential mechanism of platelet activation in response to infection is possible. Indeed, infection triggers a systemic inflammatory response, which may lead to direct platelet activation or thrombin generation. There is evidence that inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8 can activate platelets [15, 16]. However, activated platelets are also an important source of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Inflammation and coagulation are directly linked in a bidirectional manner and thus inflammation leads to thrombin generation in a tissue factor-dependent manner. This thrombin generation leads to fibrin clot formation but also platelet activation and consumption. These observed changes can explain the increase in platelet indices (MPV, PDW and PCT) with COVID-19 severity as in our study.

These simple parameters can be used for early diagnosis and identification of severely ill patients. Indeed, MPV is thought to be a marker of platelet function and activation linked to COVID-19. In general, platelet production increases as the platelet count decreases. Immature platelets represent a hyper-reactive platelet population associated with thrombotic events.

The PDW still appears to be the most specific marker of platelet activation during COVID-19. During activation, to obtain a larger surface area, the platelets change their discoidal shape into a spherical one. At the same time, the formation of pseudopodia occurs. The increase in the number and size of pseudopodia can affect PDW. Increased PDW is thought to be associated with an unfavorable course of COVID-19 disease. Therefore, the diagnostic value of PDW in COVID-19 needs to be further investigated with larger patient cohorts to establish the sensitivity and specificity of this parameter. Elevated PDW is a significant factor in the poor prognosis of COVID-19 disease. Our study showed that the PDW values were significantly increased in patients with severe COVID-19.

A similar distribution is reported by Guclu et al in their study, at admission, the MPV was higher in severe compared to non-severe forms (9.61 vs. 9.18), and the same is true for the PDW values (17.72 vs. 17.37) [12]. The same trend was observed for mortality, with platelet indices, MPV and PDW, found to be higher in non-survivors at admission. According to this study, a one-unit increase in MPV increases mortality by 1.76 times [12]. The mechanism of change in platelet indices in COVID-19 patients is probably multifactorial. Three hypotheses related to platelet count and structure are proposed for COVID-19. Firstly, as with other coronaviruses, thrombocytopenia may be due to bone marrow infection. Secondly, the destruction of platelets by the immune system. Thirdly, platelet consumption is due to aggregation in the lungs. In addition, the increase in PDW may be due to the dysregulated expression of inflammatory cytokines, the aberrant increase in neutrophils or the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) caused by the mechanism of SARS-COV-2 infection [17, 18].

Overall, as suggested by several studies on the phenotypic and transcriptomic characterization of platelets in COVID-19, the results obtained may be explained by the fact that SARS-CoV-2 modulates platelet number and size by modulating megakaryocytes and platelet gene expression [19].

Limitations

This study has some limitations. Firstly, it is a retrospective study and the platelet count tests for each patient had different time intervals between them. Secondly, this study focused on the exploration of platelet counts and indices, so data on other blood count parameters and chronic diseases such as diabetes were not reported. Thirdly, this was a single-center study. Further studies with variables parameters are needed to confirm our results.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the platelet count and its indices may be rapid, cost-effective and interesting markers in the risk stratification of COVID-19 disease. According to our observations, PDW would be an important marker both in the risk stratification of severity but also in the prognosis and adverse outcome of COVID-19.

To show more clearly the strength of these parameters, we would like to substantiate our findings on a larger number of patients, especially through multi-center studies, and develop a scoring system using these parameters to predict the evolution of COVID-19.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Conflict of Interest

All authors certify that they have no affiliation or involvement with any organization or entity having a financial or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Abou Koundio and Marie Lea Kabou. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Abou Koundio and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

| References | ▴Top |

- Wang W, Tang J, Wei F. Updated understanding of the outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Wuhan, China. J Med Virol. 2020;92(4):441-447.

doi pubmed - Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, Wang B, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061-1069.

doi pubmed - Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Xia J, Liu H, Wu Y, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):475-481.

doi pubmed - Mishra S, Jaiswar S, Saad S, Tripathi S, Singh N, Deo S, Agarwal M, et al. Platelet indices as a predictive marker in neonatal sepsis and respiratory distress in preterm prelabor rupture of membranes. Int J Hematol. 2021;113(2):199-206.

doi pubmed - Fan BE. Hematologic parameters in patients with COVID-19 infection: a reply. Am J Hematol. 2020;95(8):E215.

doi pubmed - Ji Y, Ma Z, Peppelenbosch MP, Pan Q. Potential association between COVID-19 mortality and health-care resource availability. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(4):e480.

doi pubmed - Khurana D, Deoke SA. Thrombocytopenia in critically ill patients: clinical and laboratorial behavior and its correlation with short-term outcome during hospitalization. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2017;21(12):861-864.

doi pubmed - Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, Gong J, Li D, Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1094-1099.

doi pubmed - Lippi G, Plebani M, Henry BM. Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: A meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;506:145-148.

doi pubmed - Yang M, Ng MH, Li CK. Thrombocytopenia in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (review). Hematology. 2005;10(2):101-105.

doi pubmed - World Health Organisation (WHO): Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Situation Report-84, Apr. 2020.

- Guclu E, Kocayigit H, Okan HD, Erkorkmaz U, Yurumez Y, Yaylaci S, Koroglu M, et al. Effect of COVID-19 on platelet count and its indices. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2020;66(8):1122-1127.

doi pubmed - Demir D, Ocal F, Abanoz M, Dermenci H. A case of thrombocytopenia associated with the use of hydroxychloroquine following open heart surgery. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5(12):1282-1284.

doi pubmed - Butt MU, Jabri A, Elayi SC. Azithromycin-induced thrombocytopenia: a rare etiology of drug-induced immune thrombocytopenia. Case Rep Med. 2019;2019:6109831.

doi pubmed - Zheng M, Karki R, Williams EP, Yang D, Fitzpatrick E, Vogel P, Jonsson CB, et al. TLR2 senses the SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein to produce inflammatory cytokines. Nat Immunol. 2021;22(7):829-838.

doi pubmed - Keane C, Tilley D, Cunningham A, Smolenski A, Kadioglu A, Cox D, Jenkinson HF, et al. Invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae trigger platelet activation via Toll-like receptor 2. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(12):2757-2765.

doi pubmed - Yan Q, Li P, Ye X, Huang X, Feng B, Ji T, Chen Z, et al. Longitudinal peripheral blood transcriptional analysis reveals molecular signatures of disease progression in COVID-19 patients. J Immunol. 2021;206(9):2146-2159.

doi pubmed - Middleton EA, He XY, Denorme F, Campbell RA, Ng D, Salvatore SP, Mostyka M, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps contribute to immunothrombosis in COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. Blood. 2020;136(10):1169-1179.

doi pubmed - Barrett TJ, Bilaloglu S, Cornwell M, Burgess HM, Virginio VW, Drenkova K, Ibrahim H, et al. Platelets contribute to disease severity in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2021;19(12):3139-3153.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Clinical Infection and Immunity is published by Elmer Press Inc.